When I saw “I, Borg” for the first time, back when it originally aired, I considered it to be the best episode TNG had ever given us. I wouldn’t go quite that far anymore, but it has retained a place on my personal “top five” (or so) list ever since. This one absolutely knocks it out of the park: heady ideas, weighty themes, and character choices that threaten to go quite dark, yet remain believable and true to who the characters are. In the end, the “message” also stays true to classically Trekkian ideals, but not at all in an easy or taken-for-granted way; this is an episode that’s about testing and challenging those ideals, and sticking with them even when doing so is uncomfortable and frightening (and in the long run, possibly even suicidal). Showrunner Michael Piller is quoted in the TNG Companion as calling this episode “everything I want Star Trek to be,” and I have always wholeheartedly agreed with this sentiment.

I have also always said that, following “The Best of Both Worlds,” this was the exact right next direction to take with the Borg, both in a plot sense and in a thematic sense. Plot-wise, BOBW was edge-of-your-seat epic on a level that could scarcely be topped, and any attempt to do so would likely have fallen flat. Our heroes (and the writers) pulled a rabbit out of a hat and found a way to defeat the overwhelming threat of the Borg once, and even that strained credibility; trying to do so a second time could hardly have fared as well. But also, as I’ve discussed elsewhere, Star Trek is not a show that is fundamentally about implacable foes and epic space battles and blowing the bad guys to pieces. Previous Borg episodes worked precisely because the exceptional nature of the Borg allowed the show to flirt with playing against type, but there comes a point when you have to engage with the threat that the Borg represent on a more intellectual and ideological level—not their threat to the Federation’s survival, but their threat to its ideals. How does a peaceful federation of diverse worlds, dedicated to tolerance and inclusivity and embracing “new life and new civilizations,” come to terms with the existence of an adversary that explicitly seeks to eradicate individuality and self-determination, assimilating everyone into a single homogeneous collective? We’re not going to just lie down and let them, of course. That’s not in question. But if we hit upon a way to preserve ourselves by destroying them—specifically, by using an essentially innocent individual as an instrument of our collective will and his own people’s destruction—can we really do that, without kind of becoming them?

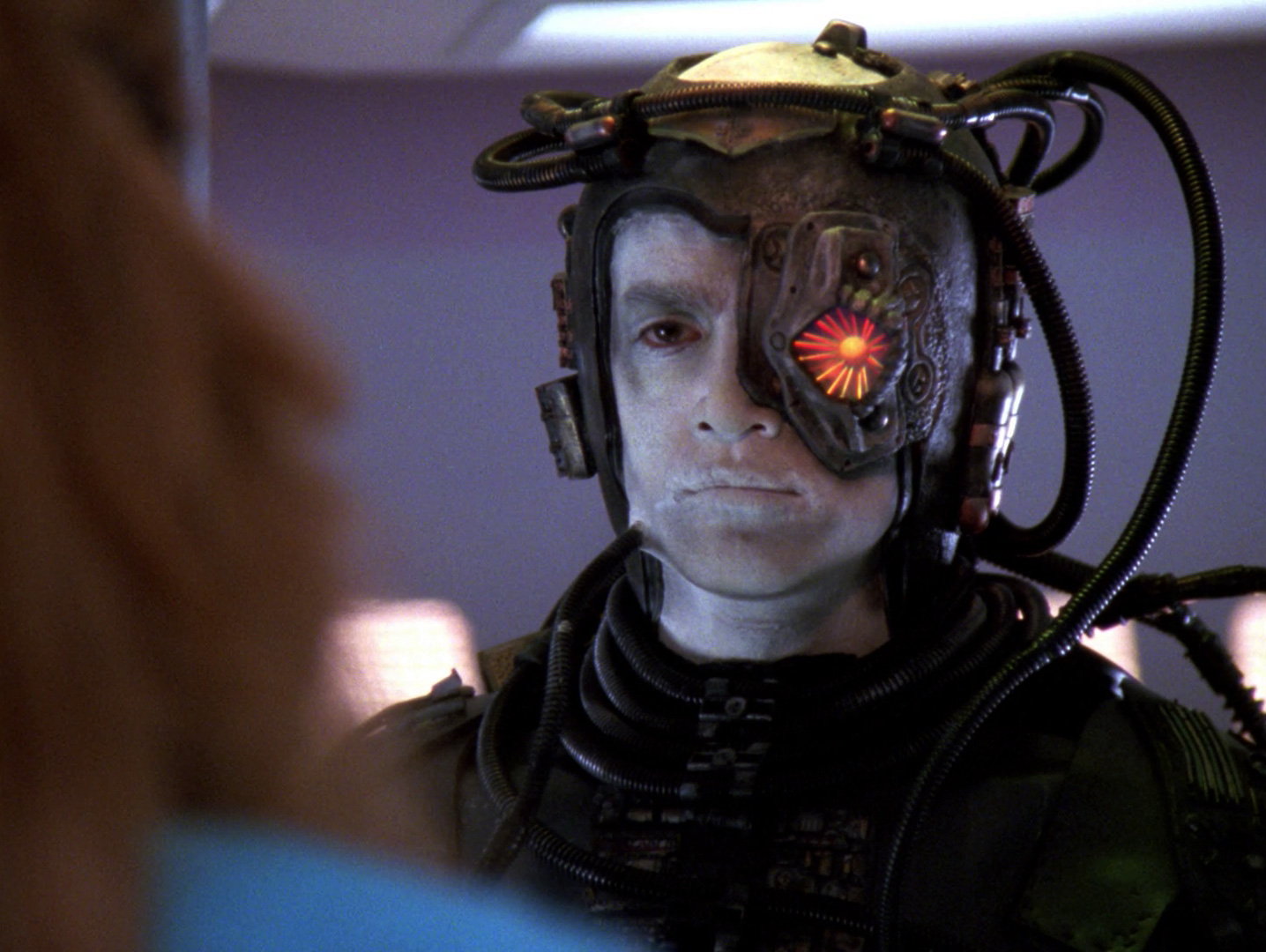

Speaking of playing against type, a big chunk of the awesomeness of this episode stems from watching two key characters do precisely that. One of them, of course, is Picard. As soon as it becomes clear that we’re watching a Borg story, our interest is naturally piqued—but when Captain Picard, our exemplar of 24th-century humanity, who so often serves as the mouthpiece and moral center of the show, conceives a plan to use the captured Borg survivor as a weapon to effect the destruction of the entire collective? That is a dark, compelling, and powerful moment! Yet it’s also a believable one, for several reasons: First, the Borg really do represent an existential threat, so it’s not too hard to understand why our hero might contemplate such a measure. Second, their very nature as a collective of drones lacking individual identities makes them uniquely easy to dehumanize. But also, and most importantly, our captain is of course dealing with the aftereffects of a profound trauma, having had his own humanity and individuality forcibly stripped away from him by the Borg. He assures Troi early on that he’s “quite recovered” from that ordeal, but even Data can see that this is not so (more on that later). He’s still Picard, so his outward behavior remains characterized by calm restraint for most of the episode, but his demeanor is unusually cold and detached at several points, and under provocation, he gives himself away even more transparently to Guinan with the line “It’s not a person, dammit, it’s a Borg!” Seeing this side of Picard is a deliciously uncomfortable experience. Yet he also remains himself; he’s not abandoning his ideals, just compartmentalizing so that he doesn’t have to apply them here, and the subtle shifts in his demeanor show his underlying discomfort with it. And then there’s Guinan, whose behavior is in some respects even more discordant with what we’ve come to expect from her. Picard, for all his humanitarian ideals and principles, is after all a starship captain, and has shown himself fully capable of grappling hard-headedly with harsh military realities on plenty of occasions. But Guinan is a bartender, and a “listener” (as Geordi pointedly reminds her in this episode), and normally represents the show’s ethos of inclusivity and tolerance more than anyone. Whenever someone on the ship is troubled by feelings of not belonging, or not having a right to be who they are, Guinan is the one who builds them up. It was Guinan who helped Picard to wrap his brain around the full ramifications of Bruce Maddox’s dehumanization of Data, Guinan who convinced him to give Ensign Ro a fair hearing, and Guinan who pushed Geordi to embrace the differentness of Reginald Barclay. Yet she also, of course, is a refugee whose people were all but destroyed by the Borg, and in this episode, she initially takes an even harder line than Picard with respect to the rescued Borg survivor. It’s shocking, but it’s also wonderfully humanizing for a character who can sometimes come across as irritatingly smug and holier-than-thou. I particularly enjoy the scene in which Geordi turns the tables on her (in light of scenes between the two of them from several past episodes, including the Barclay and Ro ones that I just referenced but also “Galaxy’s Child” in regard to Leah Brahms), for once challenging her to look past her prejudice and see the truth of another person. From there, to her scene with Hugh himself, to the subsequent scene in which she relates her thoughts to Picard and challenges him, in turn, to also look the prisoner in the eye and reckon with what they’re about to do, she goes through a quick but remarkable arc that serves as the backbone of the entire episode. Still, it feels as though the captain himself is going to be the harder sell, both because his trauma at the hands of the Borg is much more personal and recent and because, in the end, the buck stops with him in terms of what actions to take or not take. I appreciate the fact that, even though they (necessarily) happen pretty quickly, both characters’ changes of heart occur in response to specific things that they hear from Hugh, and thus actually feel earned in a way that these kinds of turnabouts too often don’t feel. For Picard, of course, this takes the form of the awesome scene in his ready room in which he play-acts the role of Locutus of Borg, and pokes at Hugh until the latter dramatically asserts himself in resistance. Even though the idea makes basically no sense, who among us did not, upon first watching this scene, experience a surge of delicious dread at the possibility that somehow, the captain really was still Locutus? He adopts the persona so unexpectedly, out of nowhere, almost as though some kind of long-buried conditioning is resurfacing. You know the show isn’t going there, and you don’t actually even want it to…but still! But even with full knowledge that nothing of that sort is going on, just watching Picard and thinking about what he must be feeling, and all the things going through his head, as he assumes this identity and mouths these things that were once forcibly imprinted over the truth of who he is….and then to have the hated, dehumanized Borg prisoner show resistance to them! And finally, the big moment where Hugh lays implicit claim to his own individuality, calling himself “I” and rejecting his Borg-ness? Damn. Cool stuff. (I didn’t quite put this together on my own, but what Picard is basically confronting here is the prospect of using Hugh in the same way that the Borg used him. For him, that’s the crux of the moral choice before him, much more than whether or not wiping out the Borg is defensible in general.)

As with any episode, there are nitpicks. One minor but galling one detracts a bit from the awesome scene over which I have just been gushing; if you pay attention, you’ll notice that Hugh actually refers to himself singularly once earlier in the episode (asking Geordi “Do I have a name?”). Clearly, this was an error by the writers that somehow no one caught. It’s pretty easy to overlook, but I still wish it weren’t in there! More significantly, the whole notion of a paradoxical, un-analyzable geometric shape being something that, when uploaded into the Borg collective, will somehow undo them, is patently silly. I think the right move here would have been to avoid getting too specific about the nature of the invasive program—an idea that was compelling in the abstract, but falls apart as soon as the episode tries to flesh it out. It harks back to the silliness of the original Trek episode “I, Mudd,” in which Kirk and Spock cause the computer brains of a bunch of robots to conk out by saying illogical things to them. (Remarkably, I had never made the connection, until this very moment, of the similarities in the titles between these two episodes. Was there an element of intentional reference here!?) And if computers can’t cope with Data and Geordi’s paradoxical shape, then why does it not seem to threaten the ship’s computer—or, for that matter, Data himself? It’s pretty dumb.

In the end, Picard and company come around to the humanitarian point of view and choose not to use Hugh to destroy the Borg. Are they right not to do so? They are, of course, “our heroes,” and the show usually expects us to understand their choices as admirable, but arguably, “I, Borg” leaves this question somewhat up to the audience. The Borg don’t really feel like an imminent threat to the Federation at this point in the series, given that until now, they hadn’t been seen since “The Best of Both Worlds”—but from the characters’ perspectives, they absolutely could show up again at any time, and their doing so might well spell doom for them and their entire civilization. Does that possibility justify an act that the episode presents, at least, as amounting to genocide? Is it really, ultimately, them or us? And then, too, the episode ends on a wonderfully ambiguous note with regard to the outcome of sending Hugh back to the collective with his newfound sense of individuality—possibly “the most pernicious program of all,” as Picard speculates. (Here again, one can nitpick. Doesn’t every newly assimilated person possess a similar individuality, which the collective is obviously perfectly capable of eradicating? But, whatever.) This idea amounts to defeating the Borg ideologically in lieu of destroying them physically, in recognition that doing the latter would amount, in a sense, to becoming them ideologically, which is clever and on-theme. (Implicitly, there are all kinds of competing definitions of “assimilation” floating around in this episode.) But will it work? Does Hugh retain his sense of self upon returning to the collective (and if so, will this have any effect on the Borg as whole, as Picard hopes)? Forget about what future episodes do with these questions; here, we get no answers, no pat resolution, and the ambiguity makes the ending that much more compelling.

One small final observation (to which I briefly alluded above): This is something that I don’t recall ever noticing before, but there’s an interesting moment very early in the episode, right after Picard makes the decision to allow Dr. Crusher to beam the Borg survivor aboard for medical treatment and then beats a hasty retreat to his ready room. In the scene after this, Troi follows him and tries to get him to talk about his feelings about the situation, in light of his past trauma at the hands of the Borg. But notice how, when the captain abruptly leaves the bridge (without even verbally handing off command to another officer, as he usually would), Data turns around and shoots Troi a significant look, and it appears to be this that then prompts her to follow Picard into his ready room. Data, of course, is at this moment the ranking officer aboard the ship after the captain, since Riker is down on the moon, so in a sense, it’s natural for him to take the initiative here—but at the same time, one gets the impression that our emotionless android is the one who first picks up on the fact that the captain may be emotionally compromised, and that he actually has to call the counselor’s attention to the matter! This reflects pretty poorly on the supposedly empathic counselor, but I love it as a wonderful little moment for Data.

This episode rocks.

You note two ways that the episode portrays Troi poorly. First, as you call attention to, at the end that she doesn’t pick up on what’s going on with Picard. Second, Guinan serves the function Troi should really be serving. Of course, in this episode, Guinan’s past history with the Borg makes her fit much better in this role. Still, the existence of Guinan on the ship is somewhat redundant with a counselor, and it’s one of a bunch of reasons Troi never emerged as a compelling character.

I do love this episode, but I really don’t find it quite plausible that separating a Borg drone from the collective would be enough in itself to give it a sense of individuality, since presumably this sort of thing would happen from time to time and the Borg would know how to deal with, and it somewhat undercuts their fearsomeness. It’s even less plausible to me that Hugh would retain such an identity when returning to the collective (though that is not explored here, the characters entertain it as a reasonable possibility). I think I’d buy it more easily if, say, Geordi had engaged in a pet project to do this to the Borg, perhaps against Picard’s wishes? I dunno if that makes sense. Even some kind of rogue electical charge, which, while not quite satisfying either, would at least introduce a factor that suggests that de-borgifying someone was as easy as doing… nothing. I wish we had some reason for this to happen.

Also, before they hit on the option of “infecting” the collective with individuality, for a while of course they were considering attempting to wipe out the collective with the impossible shape. Putting aside what you say about his not really making much sense, and assuming as you suggest that they framed this as devising some kind of trojan horse program—if it’s a question of whether they should have attempted to wipe out the Borg, the answer in my view is OBVIOUSLY YES. The Borg are essentially one person (later nonsense about a queen aside) with many bodies. And who is that person? Essentially an incredibly powerful homicidal maniac bent on killing *every species they encounter* in a brutal and dehumanizing way as a part of a plan to dominate the galaxy. We killed plenty of Nazis in order to save ourselves (and others) without much sweating it, and not only were they a much smaller scale of a threat than the Borg (even if that’s only because 20th century Earth is a lot smaller than the Trek universe), there was a LOT more gray area there about the individuality and culpability of individual Nazis as a part of a larger system in which people were incentivized to behave terribly. It seems pretty obvious to me that Picard should have been willing to use almost any means necessary to destroy the Borg. Not doing it because you would violate the autonomy of one person who only recently even became a person strikes me as utterly insane… though also, I have to admit, quite consistent with the spirit of Trek.